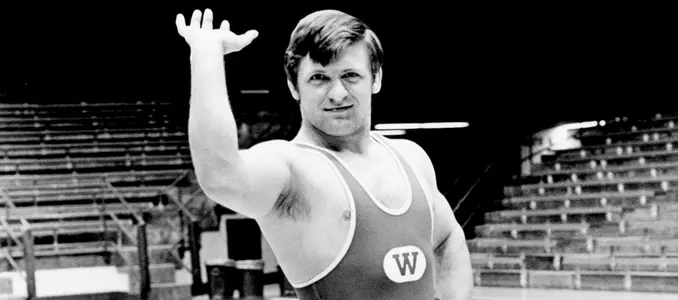

2016 Hall of Fame: Rick Lawinger

August 26, 2016 | General News, Wrestling, Mike Lucas

Hard work paved way for Badgers’ first NCAA wrestling champ

|

||

|

BY MIKE LUCAS

UWBadgers.com Senior Writer

Featured in Varsity Magazine

The prospect of becoming Wisconsin's first national champion in wrestling never crossed Rick Lawinger's mind. Not even close. Not while growing up on a dairy farm south of Mineral Point.

Truth is, he didn't pay attention to sports, any sports, let alone wrestling. And he wasn't even sure that he would go on to college. No one in his family had.

Lawinger was too busy with chores and milking cows with his brothers to think about anything that might distract him from the work at hand. And there was always plenty of work around the farm.

"I went to the barn at age 5," he said. "But I couldn't pick up the milk pail. It was too big."

So his dad went into town and purchased two smaller pails. Problem solved.

"That's how I got started in the cow milking business," said Lawinger, laughing. "Our farm was only a couple of hundred acres but we milked a lot of cows … around 120.

"At one time, we had the largest bulk tank (a storage tank for cooling and keeping milk) in Iowa County. I didn't get to go out for any sport until my dad sold the cows when I was in eighth grade.

"I didn't play Little League (baseball) or any of that. I was always baling hay and working on the farm. I didn't know much about wrestling – only that I had a cousin who finished second in the state."

It didn't take long for Lawinger to get up to speed on the mat.

At Mineral Point High School, he came under the wing of Hall of Fame wrestling coach Al Bauman. As a freshman, he made the jayvee team. As a senior, he won a state title. That was his growth spurt.

Crediting Bauman for his development, he said, "He taught you mental toughness. He taught you to believe you could beat anybody and he expected you to. He was a great motivator.

"Over the years, I've been in Olympic training camps with Dan Gable and other guys and Al Bauman was the best motivator I've ever been around."

As he neared graduation, Lawinger was all set to accept a wrestling scholarship to Minot (N.D.) State when Bauman intervened and pointed him in another direction.

"He told me that I should go to the UW – he thought I could become their first national champion," said Lawinger. "That didn't mean much to me at the time."

Plus, it didn't make sense to turn down a full ride since he would have to borrow money to attend Wisconsin in order to fulfill Bauman's expectations. He really didn't have any of his own.

"I was just a country kid, a farm kid," he said. "I didn't understand all of those things. But I knew how to work hard. Mr. Bauman worked you like you were in a Marine training camp."

Lawinger took Bauman's advice and committed to George Martin, a veteran of well over 35 years at Wisconsin. But he never competed for Martin, who drowned in a canoeing accident. He was 59.

"I realized I could focus and I was confident. That was the big thing. No one knows for sure they're going to win. But you can get to where you know you can win."

"That was a shock," Lawinger said. "I had never gotten to know him well. But he recruited me."

So did UW-Oshkosh head coach Duane Kleven, who wound up replacing Martin in Madison. "Duane just meant the world to me," Lawinger said. "I had total faith in him."

Kleven knew that he couldn't lure Lawinger to Oshkosh, not when he was devoted to becoming Wisconsin's first national champion, a crusade that was later aided by the presence of Russ Hellickson.

"Russ would work out at the end of the UW wrestling room with the heavier weights," he said of Hellickson, who won a silver medal in freestyle wrestling at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal.

"Those were heady times. Those were the days when Ben and John Peterson won Olympic medals and we had wrestlers in and out of there (the room) that were the best in the world."

Hellickson's profile was indisputable. Meanwhile, Kleven elevated the program to new levels.

"He understood the importance of toughening up our schedule," Lawinger said, "and not to be afraid of the Oklahoma's and Iowa's but to expect that you could beat them.

"There was a period where Duane had as many national champions as Iowa did. He was going toe-to-toe with them and he was doing it with Wisconsin kids for the most part.

"Of course, they recruited Lee Kemp the year after I left and that set a whole new standard, too. It was the birth of the program, a coming of age at the national and international scale. It was exciting."

As a freshman, Lawinger didn't get to nationals. As a sophomore, he got there but didn't place. As a junior, he lost to Michigan's Jarred Hubbard in the 150-pound NCAA finals.

This was after Lawinger had beaten Hubbard at the Big Ten meet.

Rather than bump heads with Hubbard again, Lawinger dropped to the 142-class as a senior. Kleven wasn't sure what to make of his decision and the wisdom in cutting so much weight.

"Rick, you wrestled at 145 in high school," he pointed out.

"I don't care," he countered. "I'm going down."

That summer, Lawinger had wrestled in the World University Games and the food was so bad that he lost a bunch of weight. "After I got sick over there," he said, "I realized I could get down to 142."

Despite winning his second Big Ten title, he struggled, which was completely understandable. Kleven remembered talking with Lawinger the Sunday morning after the conference meet.

"He ran up to my car and I said, 'Rick what are you doing?'"

"Coach, I just ran five miles. I got nationals next week."

Kleven realized then Lawinger was not about to let anything get in his way of winning a national championship. And he didn't. Lawinger beat Oklahoma State's Steve Randall, 8-2, in the 1974 finals.

"He said, 'Coach, I'm going to win' – he was just so confident," Kleven said. "That guy (Randall) had a move that he hadn't seen a lot of. But he adjusted to it and beat him pretty handily."

What did it mean to Lawinger to be Wisconsin's first NCAA titleholder?

"It took awhile for it to settle in," said Lawinger, whose brother Steve was a UW-All-American in 1977. "I didn't fool myself. I wouldn't have been able to do it without the background that I had.

"That was Al Bauman and the Mineral Point wrestling tradition; the expectations and the confidence he gave you. And it was Duane taking over at the UW at that time. It was all instrumental."

Decades later, Lawinger still can recall the details of one match. And it wasn't against Randall or Hubbard. It was against Iowa's Chuck Yagla, a two-time NCAA champion.

"There were only five seconds left on the clock and I knew I was going to beat him," he said. "We were on the edge of the mat and I knew he was going to take a bad shot and he did.

"And I took him down. It was a real confidence thing with me. I knew that I was on as good of a plane as I could be mentally.

"I realized I could focus and I was confident. That was the big thing. No one knows for sure they're going to win. But you can get to where you know you can win.

"I understood myself. I understood who I was wrestling. I understood what the situation was. There was a lot of clarity to it all."

As there is now for his supporters from Mineral Point and River Valley, where he coached for six years. A lot of those people – "Lifelong friends," he said – will be celebrating his Hall of Fame induction.

"They'll all be there cheering for him – the whole town," Kleven predicted. "It's typical of Mineral Point. They get behind everything."

The timing is good. Lawinger just turned 64. "I had a stroke last May, and I'm working my way back out of it," he said. "It's a mental thing. I need to build my endurance.

"I've got to get tough like the old days and just make darn sure I'm doing the walking and the workouts and the rehab."

The public recognition of a Hall of Fame career may even accelerate the recovery.

"I've got four kids and eight grandkids, and this means a lot to me," he said proudly. "I'm very appreciative of the honor and I feel very good about it."

It's something he can treasure until the cows come home.